In the 19th century, Bardhaman (Burdwan), a princely state in Bengal, emerged as a significant center for hybrid art forms born from the interaction between Indian traditions and British colonial influence. One such artistic movement was the Company Style portraiture, a genre that flourished during British rule, characterized by a blend of Mughal miniature aesthetics and European naturalism. Bardhaman’s royal family and aristocracy became key patrons of this style, commissioning portraits that celebrated both their regal identity and their adaptive modernity.

Company Style paintings often featured Indian subjects—mostly royalty, courtiers, and nobles—depicted with European techniques like perspective, shading, and realistic anatomy. In Bardhaman, this translated into striking portraits of the Maharajas and Maharanis adorned in rich garments, standing against European-style interiors or garden backdrops. These works reflected not just individual likeness but also social power, political alliances, and a fascination with Western modes of visual storytelling.

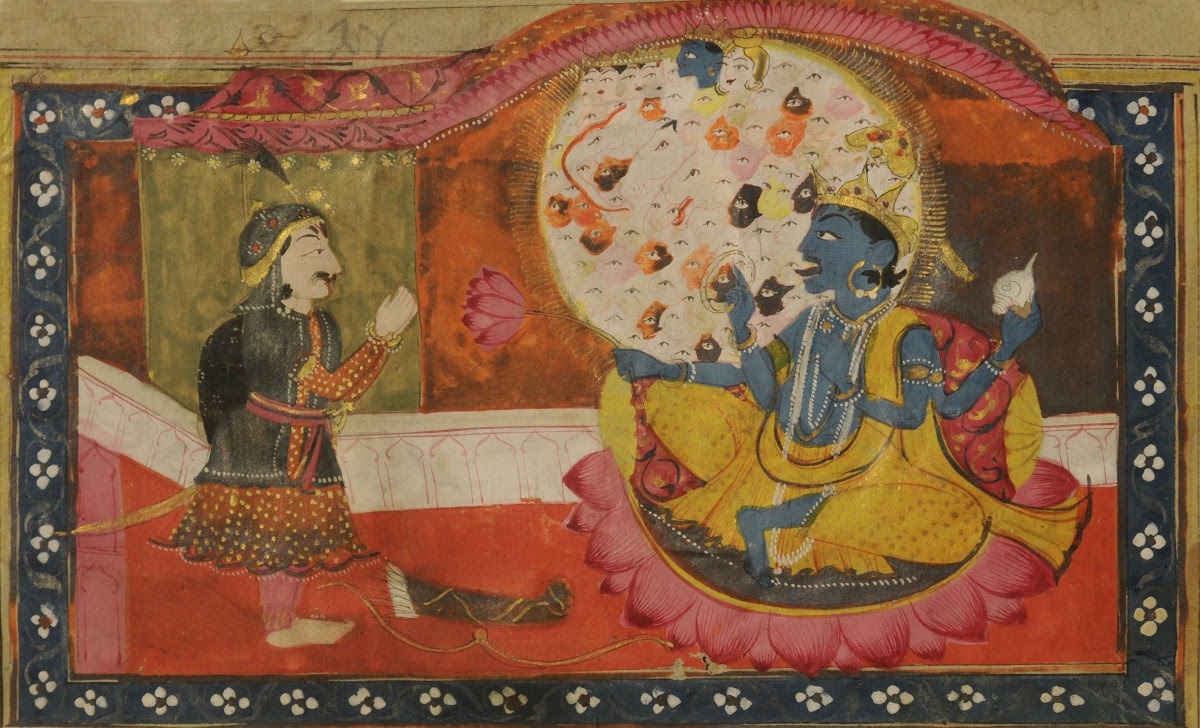

A prominent example is the portrait of Maharaja Mahtab Chand Bahadur of Bardhaman, rendered in delicate watercolor on ivory. His elaborate turban, gold ornaments, and embroidered robes reflect traditional Bengali nobility, while the composition—three-quarter profile, realistic facial features, and Western lighting—reveals European influence. These portraits were not merely decorative; they served as visual documents of lineage, status, and evolving identity.

The artists behind these works were often trained in Mughal techniques but adapted their skills to new demands. They incorporated European color palettes, chiaroscuro (light-dark contrast), and even experimented with oil painting on canvas. Some were local artists mentored by British patrons or traveling painters hired for royal commissions.

In Bardhaman, Company Style portraiture became more than just a colonial import—it was a negotiation of identity. The aristocracy used these portraits to assert their sophistication and loyalty to the British while maintaining their cultural roots. This duality made the art form unique to regions like Bardhaman, where tradition and transition coexisted vividly.

Today, these portraits remain valuable artifacts, offering a window into a complex past. They remind us how art can both reflect and shape historical change—especially in a place like Bardhaman, where brushstrokes once bridged empires and cultures.